‘Is it possible that we cannot even define a specimen object-unit of a science of action without thus abandoning the role of observer and becoming a partner in a social relationship. […] If we become participants, do we lose our objectivity? If we remain mere observers, do we lose the very object of our science, namely the subjective meaning of the action? Is there any way out of this dilemma?[1]

It was in these terms that George Walsh’s magisterial 1967 review of Alfred Schutz’s 1932 phenomenological study of social science described the challenge which still faces the would-be sociologist or ethnographer in the exploded cultural environment of 2021. Can any student of culture justifiably claim that ‘their’ method of analysing a contemporary social issue is ‘value free’ (‘wertfrei’)? What is the scientific status of ‘evidence-based’ investigation into social behaviour? What is the relationship between subjectivity and objectivity? Between personal psychology and communal belonging or ‘citizenship’? Between those who consider themselves to be ‘culturally literate’ and others whom they believe to be less so? What does it mean, in any case, to be ‘culturally literate’? What ethical principle informs the relationship between the researcher and the researched, between those who create and those who take it on themselves to comment on the creativity of others? Between the colonisers and the colonised? Between atheists and the advocates of different religious creeds? Between people of different sexes? If ‘literacy’ is assumed to mean ‘the capacity to read’, what is ‘read-ability’ and to which category of object or creative action can the term be meaningfully applied? What does it mean to be ‘enlightened’ in a post-Enlightenment, post-colonial, corporately manipulated global culture which is politically divided and cripplingly unequal?

It is against the background of what Walsh refers to as this ‘unorganised manifold’[2] that the privileged position of the academically trained, post-Enlightenment, post-colonial, post-post-modern researcher has increasingly been called into question, leaving the field open to a multiplicity of viewpoints, built on a pluralistic ethos which struggles politically to accommodate socio-economic reality. This is not an attack on diversity. On the contrary, it simply underlines the fact that sociology’s claim to scientific validity is qualified at every turn by the situational construction of particular epistemologies, leaving little if any theoretical space for claims to transcendence. Michel Foucault himself confronted this paradox in 1970 in his celebrated inaugural address to the Collège de France. He acknowledged that his position in the pantheon of French scholarship was forcing him to claim transcendent authority for an open-ended, evolving theory of discourse which was itself based on the principle of reflexive, power-driven, political contingency[3].

The same challenge can be applied to current theories governing social science research methodology. Their relative shortcomings are made transparent by Schutz’s comprehensive analysis of the different factors involved in making sense of the qualities of mind that bind communities through grounded action or separate them from each other. There was only so far that he and his contemporaries could go in formulating a method capable of providing a reliable practical account of the conflicting tensions between ‘sense’ (Sinn): the feeling response of human beings to perceived reality, and ‘understanding’ (Verstehen): the cognitive operations which ‘made sense’ of humans’ perceptions in logical or rational terms. Neurological data, while physiologically valid in itself, was and still is of limited value when applied to culturally grounded facets of behaviour. While neuro-science has been the focus of psychological theory since at least the beginning of the 20th century in terms of the individual and has burgeoned of late, it is self-evident that the task becomes all the more challenging when dealing with collective ‘mindfulness’. The feasibility of pinning down and somehow measuring the process whereby individuals identify with the affective impulses which inform the perceptual processes of others is what Schutz refers to as ‘Fremdverstehen’, more recently verbalised as ‘inter-subjectivity’ and even more loosely as ‘empathy’. And then there are the further questions surrounding the links between shared feeling ‘in the moment’, the creative actions which express it, the deterministic forces of the context, the artefacts which emerge from them and the more durable symbols with which groups of different constitutions identify in different circumstances.

Phenomenological approaches which lend empirical status to shared emotion and identity are tested to destruction at moments of social fragmentation. The potential for the theorist and for the empirical researcher to ‘make sense’ of collective behaviour depends on there being a degree of stability in the way in which groups in society translate reality into symbolic terms. As industrialisation gave way to modernism, such abstract stability was a theoretical principle developed by de Saussure and applied empirically by Lévi-Strauss and the avatars of the structuralist movement. However, while universal as a principle, one of structuralism’s unfortunate consequences was that culture was all too easily characterised in national qua linguistic terms and had trouble dealing with the pragmatic reality of the everyday, especially that involving individuals and groups from mixed cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Another problem was the outsider status of the person responsible for ascribing meaning to the everyday life of another community. The capacity to ‘make sense’ of the relationship between routine behaviour and a superordinate ‘mythological’ structure vested in shared symbols: ‘read-ability’, was reserved for those with ‘educational capital’, thought by some, even now, to be collateral with the informed insight referred to as ‘cultural literacy’.

It was only with the demise of structuralism, leaving it to be superseded by the onslaught of postmodernism’s verbal, financial and symbolic liquidity that national cultural hegemony expressed in linguistic terms could be finally put to rest, though it has persisted long past its sell-by date. As Niklas Luhmann bluntly put it in 1997 ‘Es gibt kein letztes Wort’ (There’s no such thing as the last word)’[4]. As the polyphonic model developed by Bakhtin, and the theory of différance espoused by Derrida and Deleuze became more widely adopted in the West, sociological epistemology was to take a cultural turn. Affect theory, symbolic imagination, the growth of identity politics and the vagaries of academic fashion became the driving forces. Postmodernism was to insert a methodological wedge between a qualitative approach to cultural studies research and sociology’s established claim to scientific status. The counterpoint, as all of us recognise only too well, has been that the power of mathematical abstraction has hugely strengthened technology’s ability to model human behaviour and to analyse big data in quantitative terms.[5] It has followed that the pressure for qualitative sociological research to be rigorous in its procedures whilst remaining open-ended in the types of behaviour it is seeking to evaluate has, if anything, increased. As Crossick and Kazcinska put it, ‘data is not the plural of anecdote’.[6] It is this paradox which makes the incorporation of emotional iconicity into cultural studies research so hard to articulate in methodological terms: the challenge which affect theory has sought to meet over the last twenty years by drawing on the evidence of unsolicited public discourse[7].

All the above propositions place would-be project directors in the current cultural environment in the invidious position of ‘sense-maker’; they are taking on the role of ascribing meaning to the lived experience (Erlebnis) and actions (Handeln) of others, where ‘meaning’ is an incalculable amalgam of emotion and cognition at the individual level which is then extended through reiteration and symbolic translation into a shared property of culture. On the other hand, algorithmic modelling’s claim to be ‘scientific’ does not stand up to closer scrutiny when it comes to ascribing ‘meaning’ to human action. Rather It has the status of an instrumental hypothesis which can only be verified retrospectively in the light of human experience. According to this logic, it is inevitable that the social researcher be cast not as a scientist but rather as a mediator or facilitator whose task is to establish flexible, kaleidoscopic frames within which the expression of grounded experience and its translation into symbolic forms of representation become empirically representative of a given social reality. In the paradigmatic shadows of Michel Foucault and the versions of frame theory developed amongst others by Erwin Goffman and Deborah Tannen, it still remains the case that in the absence of mathematical models within which cultural collegiality can be tested (pace on-line dating and visual recognition software), a theoretical framework is discursively necessary for ‘good practice’ to be meaningfully identified and convincingly communicated to others (‘impact’). Recent experiential methodologies aimed at creating life-changing group experiences such as that exemplified by the work of François Matarasso[8], Brian Massumi and Erin Manning[9] and Dylan McGarry[10] offer ways forward whose mainstream application is work in progress. However, their sustainability in terms of lasting social change is still open to question.

To sum up the argument so far. A number of consequences have followed from the ‘de-objectivisation’ of cultural research. One is that the status of social philosophy and the hegemonic role of the trained researcher have been irreversibly undermined. The open acknowledgement that social research methodology is only as valid as the constructed status of the premise on which it is based has called into question the ethical position of the researcher and the extent of ‘their’ authority. Second, as revealed by the phenomenological investigations of the mid-20th century German school of philosophers and the modern-day avatars of affect theory, the factors causing individuals to identify with others is considerably more complex than the popular appeal to ‘empathy’ as a cultural catalyst would have us believe. Before becoming ‘cultural’, the experience of shared reality has to emerge over time as the outcome of co-creative action. Third, the speed and global outreach of mass communication fuelled by the power of international corporations have made the factual basis of scientific evidence very difficult to ascertain, making an alternative dialogic, dynamic approach more viable as a social diagnostic but challenging to achieve in practice.

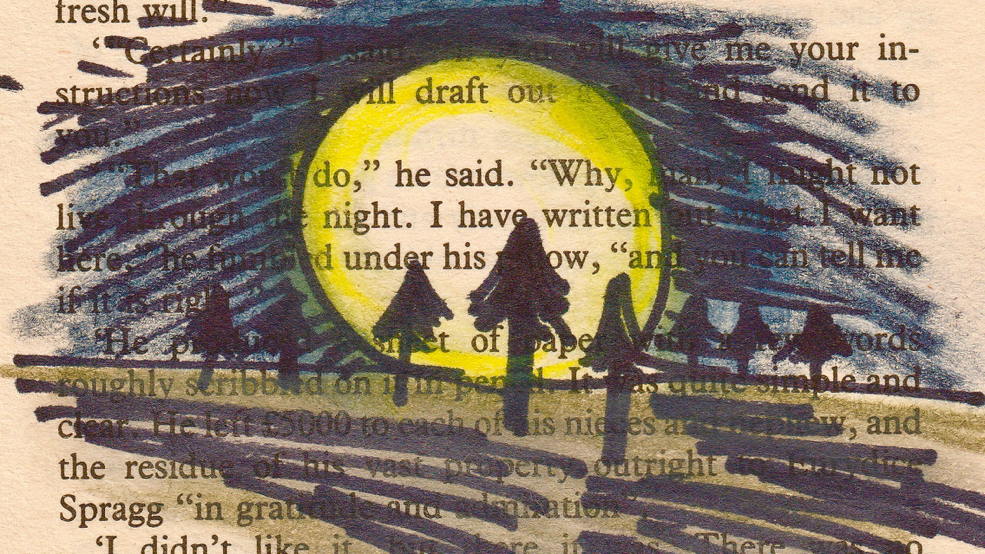

Paradoxically, in the face of such uncertainties, it is hardly surprising that university based researchers and the institutions who support their projects should insist all the more strongly on the scientific rigour of their methods. Nor that in a cultural environment dominated by the need to promote collective ‘well-being’ against a background of crisis-ridden economic and cultural disparities, the shift towards qualitative research methods should become simultaneously more widespread and ethically fragile. It is this which makes the responsibility of ‘making sense’ less exclusive and, by extension, less credible when defined in strictly scientific terms. Weber and his followers, notably Henri Bergson, Husserl and Schutz himself, were aware that while the emotional components of shared cultural values were hard to reduce to scientifically verifiable categories, they could be ‘read’ (Bergson’s term) as reflections of experience embodied in material outputs and the symbolic representations with which they were associated. Identification with totemic archetypes on the part of participant actors would allow wider inferences to be drawn about the cultural context in which they had been created and the ‘moment in time’ to which they corresponded. The complex of factors inherent in the artefact would offer pointers or aesthetic indicators which could be ‘read’. The questions remain: by whom? how? and What action should follow?

To put these questions differently: what associations exist between the structure and content, verbal or material, of artefacts and the world of lived reality to which they correspond? And conversely, what is the dynamic which causes the artefact to attain the distilled status of symbol or ‘myth’ such that it becomes a cultural point of reference or localised ‘habitus’ with which people identify? These are hardly new questions. The process of interpreting the translation of artefact into socially significant symbol has been the subject matter of research by ethnographic trail-blazers such as Lévi-Strauss and the hermeneutic (‘philological’) method applied to literary text by German scholars such as Gadamer and Spitzer for whom a specific stylistic feature or ‘etymon’ could act as the microcosm of a cultural and historical environment. A more recent analogy of this approach has been Neil Macgregor’s encyclopaedic representation of world history through the informed analysis of emblematic objects in which insight and knowledge are necessary pre-requisites. As he memorably states in the introduction to his book based on his classic series on BBC Radio 4:

‘Can we ever really understand others? Perhaps, but only through feats of poetic imagination combined with knowledge rigorously acquired and ordered’ [11]

However, as we have seen, the difference between cultural historiography and the type of methodology required by ethno-cultural studies today is that the object of study reaches beyond the attributes of the object to creative acts which have become virtualised and infinitely diversified. This demands a more pluralistic source of data grounded in the act of creation combined with an awareness of its social significance which goes beyond the act itself. The insight and intuition which accompanies what Schutz called the ‘unit of action’ (see above) extends beyond enactment to an appreciation – a ‘making sense’ – of its qualitative contribution to its context. The capacity to ‘make sense’ of creative action in terms of its social value applies as much to the actor as to the observer participant, even if the discursive idiolect in which it is articulated is different. Is the sentient singularity (oneness) of an experience sufficient for it to qualify as ‘research’? Probably not, even if for the individual concerned it may be part of a process of self-discovery. Compare Aldous Huxley’s experiments with LSD with the excitement of participation in high risk sport or the collective trance or spiritual ecstasy experienced in religious ritual or at mass sporting or cultural events? The difference is surely that Huxley’s experiment involved agency and forethought, though whether it could be described as a ‘unit of action’ in the Weberian sense is at best debatable. Similarly, to be a ‘consumer of culture’ or ‘shopper’, while it may invite reflection on its socio-economic significance is hardly in itself a creative act. To be an actor researcher must arguably involve creative initiative. In addition, a degree of reflection is needed so that the experience can in some way be relativized and understood in comparative terms. What form this process should take is, however, another key question which still remains to be answered.

Before finally considering the link between ‘making-sense’ and ‘citizenship’ as an object of research, it is worth reminding ourselves of the forces which have highlighted the need for co-participation in project design and implementation. Much has to do with a culture of ‘sensibility’, readily promoted by the combination of corporate capitalism and popular media already alluded to; much too to population mobility, ethnic diversity, and economic crisis which have together highlighted the need to improve conditions of life in otherwise divided communities. A third factor, not yet fully explored, has been the blurring of the boundaries between art, nature and everyday life. The emphasis on creativity as an end in itself has created an intercultural space in which diversity of expression and its capacity to promote social change has become paramount but open to self-abuse by artists themselves. Creative art does not exist in its own aesthetic bubble. The distinctions between high and low art, performance and installation, film and technology, art, craft and the creative actions of the everyday have been revolutionised. It is this more than anything else which, while redefining the very nature of citizenship, has made it all the more important to create experimental situations in which the expression of local voices has material as well as symbolic status and to enable these voices themselves to define the parameters of project design.

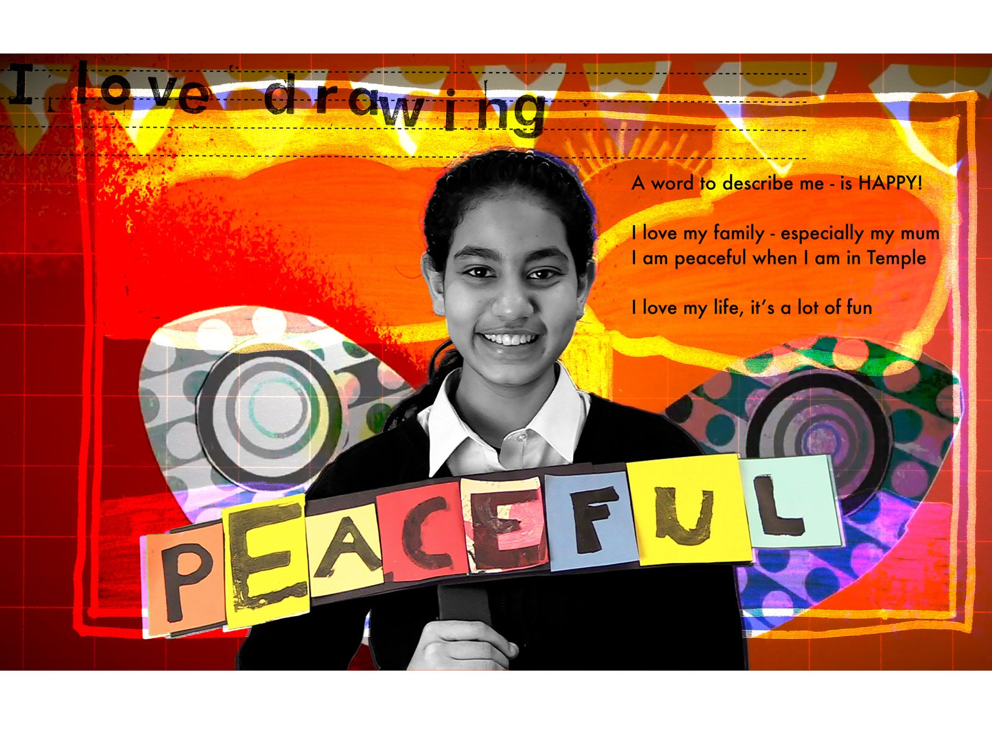

It is for all the above reasons that ‘citizenship’, cultural literacy and social research methodology have become so intimately interdependent, in practical as much as in conceptual terms; why it is no longer acceptable for centres of higher education driven by policy-led, competitive ideologies to appropriate data from fieldwork for their own theory-led ends without there being reciprocal benefits for actors on the ground who share the power to control the durable application of research processes and outcomes. Co-participation in social research is a demonstration of ‘active citizenship’ which carries with it the civic entitlement to benefit from its findings. It supersedes the intellectual dichotomy which separates ‘making sense’ from ‘sense-making’: the traditional model in which ‘citizen-actors’ provide the data and ‘trained experts’ offer the analysis according to independent priorities. Instead, creative action arises out of collectively articulated local needs: co-action which ‘makes sense’ according to its own terms and sets its own standards. The initiators of such action become catalysts: de facto ‘citizen researchers’ who enable creative opportunities to attain the status of inter-active symbols with which local populations can identify in their everyday lives.

According to the terms of this research model, ‘cultural literacy’ is removed from the exclusive realm of critical understanding. Instead, it becomes absorbed into acts of participation which are meaningful to the participants and out of which knowledge is re-generated. In such a model, the trained researcher, like the artist, becomes a co-creator. In environments marked by ethnic and cultural diversity, ‘co-creation’ means joint activity which allows meaning to emerge organically through collective learning processes within secular spaces, where experiential knowledge understood in phenomenological terms is fused with practice informed by imagination. In such research environments, ‘trained researchers’ become cultural mediators or ‘entrepreneurs’ in the best sense of the word, in that their work is informed first and foremost by social interaction which ‘makes sense’ in terms of collective fulfilment. Only then can it become translated into imaginary constructs which are emblematic of the practices which they symbolise, which are communicable to other cultural contexts to be ‘read’ and practised accordingly.

[1] George Walsh ‘Introduction’ Alfred Schutz The Phenomenology of the Social World (London: Heinemann, 1972) p.xviii.

[2] ibid. p.xvi.

[3] Michel Foucault L’ordre du discours (Paris: Gallimard, 1971) pp.7-8.

[4] Niklas Luhmann Die Gesellschaft der Gesellschaft (Frankfurt: Surkamp, 1997) p.141

[5] Geoffrey Crossick and Patrycja Kaszinska Understanding the value of arts and culture (London: AHRC, 2016) pp.156-157.

[6] Ibid p.157.

[7] Robert Crawshaw ‘Beyond Emotion: Empathy, Social Contagion and Cultural Literacy’ Open Cultural Studies December 2018 2.1 pp. 676-685.

[8] Francois Matarasso A Restless art (London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 2019).

[9] Brian Massumi Politics of Affect (Cambridge: Polity, 2015).

[10]Dylan McGarry ‘The Listening Train: A Collaborative, Connective Aesthetics Approach to Transgressive Social Learning’ Southern African Journal of Environmental Education Vol.31 2015 pp. 8-21. See also https://www.empatheatre.com/ .

[11] Neil MacGregor A History of the World in 100 objects (London: Allen Lane, 2010) p.xviii.